Pidge’s Poppies

Pidge’s Poppies

Jan Andrews

Timothy Ide

Ford Street, 2024

32pp., hbk., RRP $A27.99

9781922696380

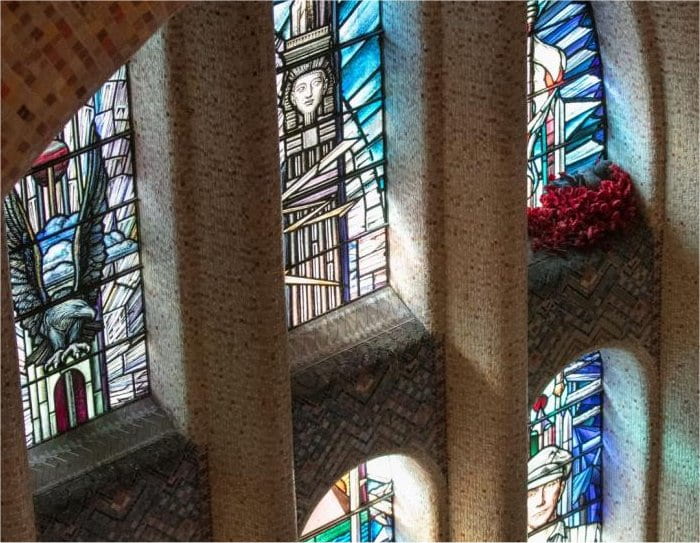

High on a ledge in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Australian Wat Memorial in Canberra, there is a blodge of bright scarlet that stands out even against the colour of the stunning stained glass windows. And if you’re lucky, your keen eye might just pick out a couple of proud pigeons in this nest made from the remembrance poppies people have placed beside the names of their loved ones in the Hall of Remembrance down below to show that they and their service has not been forgotten.

Based on a true story that took place in 2019, and bringing the story of the role that pigeons played during World War I and II to life, this is a sensitive but compelling read that offers a new perspective to the commemoration of ANZAC Day, one that acknowledges the human sacrifices made but focuses on the contribution of these little birds – the many-times great grandmother and great grandfather of Pidge and Henry- instead.

In 2019, the Australian Parliament declared 24 February each year as the National Day for War Animals, also known as Purple Poppy Day. It’s a day to pause, wear a purple poppy, and pay tribute to the many animals who served alongside soldiers and this is a poignant and stunningly illustrated tribute to all those creatures, often symbolised by Simpson’s donkey but which involved so many other species doing so many other things in so many fields. So important have they been that there is now an international war memorial for animals at Posières in France and those who have provided outstanding service or displayed incredible courage and loyalty can be awarded the Dickin Medal or the Blue Cross Medal.

Accompanied by thoughtful teachers’ notes, this would be an ideal addition to your collection, particularly if used alongside Wear a Purple Poppy, and the resources available through the Australian War Memorial including a digitised version of their popular A is for Animals exhibition and its accompanying publication M is for Mates which may be in your collection already because it was distributed to all schools in 2010. There is also an education kit available.

Sadly, too many of our students have first-hand experience of war, or have relatives currently embroiled in conflict, so the commemoration of ANZAC Day, while a critical part of the calendars of Australia and New Zealand, has to be handled in a different way, so perhaps exploring the stories of animals like Pidge’s relatives who served, and continue to do so, can put the horror at arm’s length yet still observe the purpose and solemnity of the day.